How non-violent fundamentalism can pave the way for violent extremism: From the interpretation of religious texts to the formation of absolutist worldviews

Adis Duderija

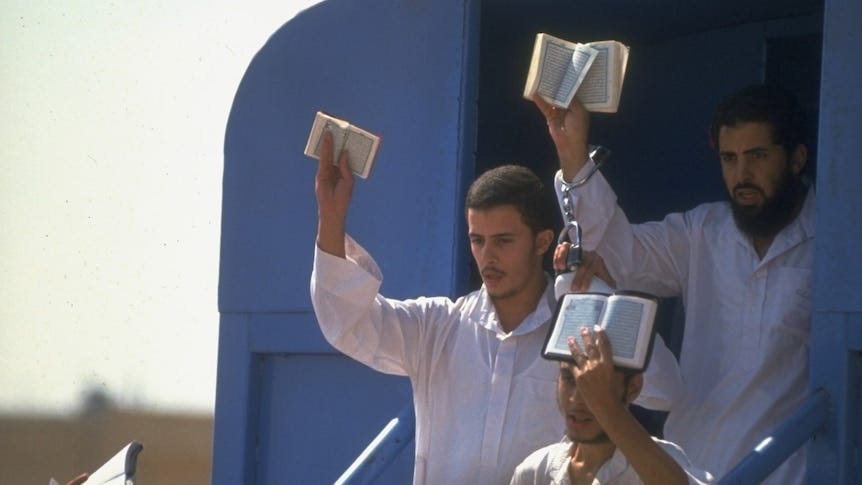

The stabbings in both Sydney and Perth earlier this year sparked yet another round of conversations around the relationship between violence and religion, in general, and Islam, in particular. It is a relationship that has been studied extensively by scholars, who have examined how certain interpretations of sacred texts can lead to worldviews that justify religiously motivated violence.

I want to look at the work of four of these scholars, and see if they can shed any light can help us understand this relationship with greater nuance and insight.

The fundamentalist paradigm

In their book The Psychology of Religious Fundamentalism, Ralph Hood, Paul Hill, and Peter Williamson argue that fundamentalism can be understood in terms of “communities of interpretation” that form around specific approaches to interpreting sacred texts. As they write:

Fundamentalism is a system of meaning rooted in the exclusive reliance on a religious text/s to interpret the world and give meaning to life.

This reliance on canonised texts as the ultimate sources of authority creates a sense of certainty and absolutism among fundamentalists. Moreover, they view their interpretation of the text as the only valid one, rejecting alternative viewpoints and largely dismissing the possibility of multiple interpretations.

In the context of the Islamic tradition, this model is particularly relevant to jihadist Salafism and other puritanical and fundamentalist approaches to Islam, where certain interpretations of the Qur’ān, hadith, and broader Islamic interpretive tradition play a central role.

The fundamentalist paradigm is based on the principle of intratextuality. According to this principle, the text alone is considered to determine its own meaning and thus should be the sole point of reference for all belief and action. This principle emphasises the self-sufficiency of the sacred text and the exclusive reliance on it for understanding the world.

By reading sacred texts intratextually, fundamentalists believe they can directly access the absolute truths contained within the text — truths which represent the ultimate authority and form the criteria for distinguishing right from wrong, good from evil. These truths are seen as immutable and unchanging, providing a sense of stability and certainty in an uncertain world. They are not subject to criticism from outside of the principle of intratextuality, for example, by means of contextualisation. Any beliefs or interpretations that fall outside the realm of what they consider to be absolute truths are viewed with suspicion and are most often disregarded.

Moreover, Hood, Hill, and Williamson highlight that fundamentalists reject the view that the sacred text is subject to interpretation by “fallible” humans. This reflects the belief in the inherent holiness, purity, clarity, and coherence of the sacred text — which is itself understood as possessing a special metaphysical origin and meaning.

Passive fundamentalism and violent extremism

While most forms of fundamentalism do not evolve into violent extremism, some do. Douglas Pratt’s work on religious fundamentalism in Abrahamic religions delves into the concept of “passive fundamentalisms” and its potential to contribute to violent extremism. Passive fundamentalism refers to non-violent forms of fundamentalist thought that exhibit rigid adherence to absolute truths but do not directly engage in violent acts. Pratt argues that this extreme belief system can create a breeding ground for violence, because it forms the foundation for more radical and extremist ideologies.

Pratt’s description on phenomenon of fundamentalism proposes a three-phase model explaining the evolution of fundamentalism into extremism and terrorism: “passive fundamentalism”, followed by “assertive fundamentalism”, and finally “impositional fundamentalism”. Each phase comprises several factors (twenty in all) which contribute to this progression towards extremism. Let me provide a brief explanation of the most relevant of these.

In the phase of passive fundamentalism, one of the factors identified by Pratt is “perspectival absolutism”. This refers to a mindset that believes in only one truth, one authority, and one correct way of being. This mindset can be rooted in various types of texts, whether political or religious. For instance, Islamic State’s condemnation of those who do not adhere to their interpretation of Islam exemplifies this factor. Similarly, right-wing extremists like Anders Breivik exhibit perspectival absolutism, in the way they consider their understanding of Islam as the only “true” version, and then proceed to equate it with fascism.

In the assertive fundamentalism phase, perspectival absolutism evolves into what Pratt calls “hard factualism”. This factor strengthens the grip on what is considered knowable, reinforcing a literalist and apodictic approach to text. In the context of Islamist extremism, hard factualism is evident in their insistence on following the “true” interpretational approach (manhaj) to Islam. Right-wing extremists similarly demonstrate hard factualism in the way they equate Islam with fascism.

Another factor in this phase is what Pratt terms “ideological exclusivism and polity inclusivism”. Ideological exclusivism refers to the rejection of any competing or variant ideological view, while polity inclusivism involves the inclusion of others within the fundamentalist movement’s frame of reference and worldview. Islamist radicalism opposes all forms of jahiliyya (“ignorance”), which encompasses anyone who has not pledged allegiance to its leader. Right-wing radicalism exhibits ideological exclusivism by identifying various groups as traitors and enemies, such as those groups and governments committed to multiculturalism. Both forms of radicalism transition from assertive fundamentalism to activism, leading to condemnatory and judgemental values directed at dissenters and opponents.

“Impositional fundamentalism”, the final phase, represents a radicalised and activist form of assertive fundamentalism, wherein extreme actions, including violence and terrorism, may be contemplated, advocated, and carried out. This phase is characterised by claims of moral superiority, the devaluation and demonisation of the Other, and the imposition of fundamentalist views on individuals and society. In the case of right-wing extremism, Breivik’s assimilation policy plan exemplifies impositional fundamentalism, in so far as it includes conditions for Muslims to remain in Europe — such as converting to Christianity, changing their names, and eradicating Islamic culture. The implicit threat of violence is present in this policy. The Global Terrorism Database provides evidence of numerous white extremist terrorism attacks during a specific period, demonstrating the willingness of right-wing radicals to engage in terrorist violence.

Similarly, Islamist impositional fundamentalism has led to numerous terrorist attacks worldwide. Islamic State, for example, aspires to global dominance based on their Salafi-jihadist ideology, claiming religious supremacy. Their emphasis on concepts like aggressive jihad and jahiliyya reveals its impositionalist nature, alongside their condemnatory language and demonisation of non-conformists.

Normalising absolutism

Pratt’s presentation of the phenomenon of fundamentalism thus outlines a sequential progression from passive to assertive and impositional fundamentalism, ultimately leading to extremism and terrorism. The factors identified in each phase help explain the transformation and provide insights into the worldviews of right-wing and Islamist radicalism.

Through numerous case studies across different religions, Pratt demonstrates the link between religious fundamentalism and violent behaviours. Pratt’s research, in this way, shows how passive fundamentalism can act as a stepping stone towards violent extremism by providing a framework for radicalisation. The rigid belief system inherent in passive fundamentalism can, as such, contribute to the acceptance of violence as a justifiable means to achieve religious goals. In this respect, Pratt writes:

What began with “normative” absolutism, that form of religious believing and concept that holds rigidly to a set of assumptions, presuppositions and ideas as absolute truth, then may evolve or emerge through a process of hardening assertion to becoming, in extremis, an impositional form of religious ideology that is expressed in terms of terrorizing behaviours and acts of violence. Many examples across different religions, both historically and contemporaneously, could be adduced to make the point.

Pratt’s findings highlight the importance of recognising the potential dangers of non-violent fundamentalism. While not directly engaging in violent acts, passive fundamentalists contribute to the broader ecosystem that supports and justifies violence. As Mark Juergensmeyer puts it, “Religion often provides the mores and symbols that make possible bloodshed — even catastrophic acts of terrorism.”

Understanding the mechanisms that drive individuals to move from passive fundamentalism to violent extremism is crucial for effective prevention and intervention strategies.

Adis Duderija is Senior Lecturer in the Study of Islam and Society in the School of Humanities, Languages and Social Science at Griffith University. He has written extensively on the Islamic intellectual tradition, interfaith dialogue, gender issues in Islam, and Islam and Muslims in the West. He is the co-editor of Shame, Modesty, and Honor in Islam.